Ethical Framework for Health Care Institutions & Guidelines for Institutional Ethics Services Responding to the Coronavirus Pandemic

Managing Uncertainty, Safeguarding Communities, Guiding Practice

Nancy Berlinger, PhD; Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH; Tia Powell, MD; D. Micah Hester, PhD; Aimee Milliken, RN, PhD, HEC-C; Rachel Fabi, PhD; Felicia Cohn, PhD, HEC-C; Laura K. Guidry-Grimes, PhD; Jamie Carlin Watson, PhD; Lori Bruce, MA, MBE; Elizabeth J. Chuang, MD, MPH; Grace Oei, MD, HEC-C; Jean Abbott, MD, HEC-C; Nancy Piper Jenks, MS, CFNP, FAANP

The Hastings Center, March 16, 2020

|

CONTENTS

|

Summary

An ethically sound framework for health care during public health emergencies must balance the patient-centered duty of care—the focus of clinical ethics under normal conditions—with public-focused duties to promote equality of persons and equity in distribution of risks and benefits in society—the focus of public health ethics. Because physicians, nurses, and other clinicians are trained to care for individuals, the shift from patient-centered practice to patient care guided by public health considerations creates great tension, especially for clinicians unaccustomed to working under emergency conditions with scarce resources.

This document is designed for use within a health care institution’s preparedness work, supplementing public health and clinical practice guidance on COVID-19. It aims to help structure ongoing discussion of significant, foreseeable ethical concerns arising under contingency levels of care and potentially crisis standards of care. Its method is to

- pose practical questions that administrators and clinicians may not yet have considered and support real-time reflection and review of policy and processes;

- explain three duties of health care leaders during a public health emergency: to plan, to safeguard, and to guide; and

- offer detailed guidelines to help hospital ethics committees and clinical ethics consultation (CEC) services quickly prepare to support clinicians who are caring for patients under contingency levels of care and, potentially, crisis standards of care.

This document is not intended to be, and should not be considered, a substitute for clinical ethics consultation or other medical, legal, or other professional advice on individual cases or for particular institutions. It reflects an evolving public health emergency; references are current as of March 16, 2020.

Foreseeing Ethical Challenges in the Care of Patients with COVID-19

Ethical challenges in health care are common even under normal conditions because health care responds to human suffering. To act ethically should be integral to professionalism in health care. However, professionals often experience uncertainty or distress about how to proceed. Cases involving patients with life-threatening illness, including those who lack capacity to make decisions concerning life-sustaining interventions and other medical treatment, often give rise to uncertainty. Institutional ethics services, such as clinical ethics consultant teams and ethics committees, respond to this practical reality by helping professionals, patients (as able), and family members to reflect on choices and make informed decisions, with reference to the rights and preferences of patients and the duties of professionals to avoid harm, benefit patients, and act fairly while maintaining professional integrity.

A public health emergency, such as a surge of persons seeking health care as well as critically ill patients with COVID-19 or another severe respiratory illness, disrupts normal processes for supporting ethically sound patient care. Clinical care is patient-centered, with the ethical course of action aligned, as far as possible, with the preferences and values of the individual patient.

Public health practice aims to promote the health of the population by minimizing morbidity and mortality through the prudent use of resources and strategies. Ensuring the health of the population, especially in an emergency, can require limitations on individual rights and preferences. Public health ethics guides us in balancing this tension between the needs of the individual and those of the group.

While all health care resources are limited, public health emergencies may feature tragically limited resources that are insufficient to save lives that under normal conditions could be saved. There is a basic tension between the patient-centered approach of clinical care under normal conditions and the public-centered approach of clinical care under emergency conditions.

In a public health emergency, first responders need clear rules to follow. Triage protocols, for example, help first responders to swiftly prioritize patients for different levels of care based on their needs and their ability to respond to treatment given resource constraints. If these rules seem unfair or cause greater suffering and distress to patients, then the burden on first responders will be excruciating. Significant moral distress is likely to arise for providers who must adhere to disaster-based protocols that require giving or withholding treatment, especially life-sustaining treatment, over the objections of patients or families.

Three Ethical Duties of Health Care Leaders Responding to COVID-19:

Plan, Safeguard, Guide

An ethically sound framework for health care organizations during public health emergencies acknowledges two competing sources of moral authority that must be held in balance:

- The duty of care that is foundational to health care. This duty requires fidelity to the patient (non-abandonment as an ethical and legal obligation), the relief of suffering, and respect for the rights and preferences of patients. The duty of care and its ramifications are the primary focus of clinical ethics, through bedside clinical ethics consultation services, institutional policy development, and ethics education and training for clinicians.

- Duties to promote moral equality of persons and equity (fairness relative to need) in the distribution of risks and benefits in society. These duties generate subsidiary duties to promote public safety, protect community health, and fairly allocate limited resources, among other activities. These duties and their ramifications are the primary focus of public health ethics.

Clinicians, such as physicians and nurses, are trained to care for individuals. Public health emergencies require clinicians to change their practice, including, in some situations, acting to prioritize the community above the individual in fairly allocating scarce resources. The shift from patient-centered practice supported by clinical ethics to patient care guided by public health ethics creates great tension for clinicians. Some clinicians frequently make care decisions across large populations. Some clinicians have training in emergency triage, and some regularly train to prepare for a range of public health emergencies. Other clinicians are less familiar with patient care in the context of a large-scale, perhaps prolonged, public health emergency.

In responding to COVID-19, an ethical framework for health care institutions should acknowledge the tension between sources of authority for health care and public health in the contexts in which these tensions are most likely to arise in clinical practice. The duties of health care leaders to clinicians and community during a public health emergency can be expressed as follows: to plan, to safeguard, to guide.

The Duty to Plan:

Managing Uncertainty

Health care leaders have a duty to plan for the management of foreseeable ethical challenges during a public health emergency. Ethical challenges arise when there is uncertainty about how to “do the right thing” in clinical practice when duties or values conflict. These challenges affect the health care workforce and how a health care institution serves the public and collaborates with public officials.

Planning for foreseeable ethical challenges includes the identification of potential triage decisions, tools, and processes. In a public health emergency featuring severe respiratory illness, triage decisions may have to be made about level of care (ICU vs. medical ward); initiation of life-sustaining treatment (including CPR and ventilation support); withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment; and referral to palliative (comfort-focused) care if life-sustaining treatment will not be initiated or is withdrawn. Triage decisions may also need to be made concerning shortages of staff, space, and supplies.

The Duty to Safeguard:

Supporting Workers and Protecting Vulnerable Populations

Health care organizations are major employers. Responding to public health emergencies includes safeguarding the health care workforce. During a surge of infectious illness amid deteriorating environmental conditions, clinicians and nonclinicians, such as maintenance staff, may be at heightened risk of occupational harms. Vulnerable populations during a public health emergency include those at higher risk of COVID-19, due to factors such as age or underlying health conditions, and those with preexisting barriers to health care access, due to factors such as insurance status or immigration status. Health care institutions that employ trainees, such as medical students and nursing students, should recognize these workers as a vulnerable population.

The Duty to Guide:

Contingency Levels of Care and Crisis Standards of Care

The tension between the equality and equity orientation of public health ethics, expressed through fair allocation of limited resources and a focus on public safety, and the patient-centered orientation of clinical ethics, expressed through respect for the rights and preferences of individual patients, is stark when life-sustaining interventions are not available to all patients who could benefit from these interventions and would likely choose them. A severe respiratory illness such as COVID-19 can require ventilator or ECMO support for critically ill patients in an intensive care unit, with ongoing monitoring by respiratory technicians and critical-care nurses. But ICU beds and staffing are scarce resources, and a surge of critically ill patients could quickly fill available beds. Shortages of many other types of staff, space, and supplies are also to be expected. First come, first served is an unsatisfactory approach to allocating critical resources: a critically ill patient waiting for an ICU bed might be better able to benefit from this resource than a patient already in the ICU whose condition is not improving.

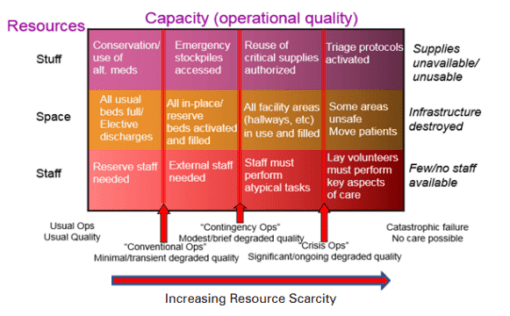

A public health emergency requires planning for and potentially implementing a range of contingencies to manage the increased demand for care and the resource scarcity. Contingency levels of care under emergency conditions unavoidably and gradually reduce quality of care due to limits on staff, space, and supplies. Infection control protocols reduce quality of care in other ways, such as by restricting visitors.

A hospital or health system’s institutional ethics services, including clinical ethics consultation (CEC), should function as resources for clinicians experiencing uncertainty and distress under normal conditions. The foreseeable uncertainty and distress that clinicians and teams will face under contingency or crisis conditions call for focused preparation by institutional ethics services; see Guidelines for Institutional Ethics Services Responding to COVID-19 below.

|

Figure 1: The Gradual Degradation of Quality as Resource Scarcity Worsens This figure illustrates the granular nature of care quality as it gradually degrades from usual care through contingency and then crisis operations, with illustrative examples of strategies used by organizations to maintain optimal quality of care at each stage despite increasingly severe shortages of staff, space, and supplies. Note that resource categories are interrelated, so shortages in one category affect other categories. For example, there may be adequate numbers of ventilators but not enough trained respiratory technicians and critical care personnel to use them. There may be a need to use crisis standards of care for some resources but not others. |

Health care institutions are crucial to our society’s ability to withstand and recover from public health emergencies. Support for ethical practice is crucial to health care integrity and the well-being of the health care workforce. Recognizing and addressing the special challenges health care workers face in responding to COVID-19 is part of health care leadership and civic duty.

|

Examples of Institutional Policies and Processes to Review or Update Using This Framework This document is designed to help hospitals, health systems that include hospitals, and community health centers conduct preliminary and ongoing discussion, review, and updating of institutional and organizational policies and processes concerning the care of patients during the outbreak of COVID-19 or another infectious disease. Relevant policies and processes include the following:

Other existing policies and processes not listed here will also require thorough review in light of emergency management conditions and local challenges. |

|

Guidelines for Institutional Ethics Services Responding to COVID-19 Clinical ethics consultation (CEC) services, clinical ethics consultants, and ethics committees should recognize duties to promote equality of persons and equity in distribution of risks and benefits in society and consider how best to support clinical practice during a public health emergency. A hospital’s institutional ethics services should prepare for service during a public health emergency.

|

For our webinar for Hospital Ethics Committees and Clinical Ethics Consultation: https://www.thehastingscenter.org/guidancetoolsresourcescovid19/

Selected Resources

COVID-19

COVID-19: Crisis Standards of Care

J. L. Hick et al. “Duty to Plan: Health Care, Crisis Standards of Care, and Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.” NAM Perspectives.Discussion paper. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine, 2020. https://doi.org/10.31478/202003b.

Italian Society for Anesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care. “Clinical Ethics Recommendations for Admission to Intensive Care and for Withdrawing Treatment in Exceptional Conditions of Imbalance between Needs and Available Resources.” English translation. March 13, 2020. https://www.academia.edu/42213831/English_translation_of_the_Italian_SIAARTI_COVID-19_Clinical_Ethics_Recommendations_for_Resource_Allocation_3_6_20.

COVID-19: Obstetrics Care

Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. “Interim Considerations for Infection Prevention and Control of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Inpatient Obstetric Healthcare Settings.” February 18, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/inpatient-obstetric-healthcare-guidance.html.

COVID-19: Health Care Workforce and Medical Students

J.G. Adams and R. M. Walls. “Supporting the Health Care Workforce during the COVID-19 Global Epidemic.” JAMA. March 12, 2020. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763136.

A. Whelan, G. Young, and V. M. Catanese. “Medical Students and Patients with COVID-19: Education and Safety Considerations.” American Association of Medical Colleges. March 5, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-03/Role%20of%20medical%20students%20and%20COVID-19-FINAL.pdf.

Crisis Standards of Care, Resource Allocation, Ventilator Allocation

National Academy of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine)

Institute of Medicine. Crisis Standards of Care: Lessons from Communities Building Their Plans: Workshop in Brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2014. https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/PublicHealth/MedPrep/2014-APR-02/Workshop-in-Brief.aspx.

Institute of Medicine. Crisis Standards of Care: A Toolkit for Indicators and Triggers. Report brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2013. https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2013/CSC-Triggers/CSC-Triggers-RB.pdf.

Institute of Medicine. Engaging the Public in Critical Disaster Planning and Decision Making. Workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2013. https://www.nationalacademies.org/HMD/Reports/2013/Engaging-the-Public-in-Critical-Disaster-Planning-and-Decision-Making.aspx.

Institute of Medicine. Crisis Standards of Care: Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response. Report brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2012. https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2012/Crisis-Standards-of-Care/CSC_rb.pdf.

Institute of Medicine. Guidance for Establishing Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations: A Letter Report. Report brief.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2009.

https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2009/DisasterCareStandards/Standards%20of%20Care%20report%20brief%20FINAL.pdf.

B. M. Altevogt et al. Guidance for Establishing Crisis Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations. Emergency Books, 2. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2009. https://www.inovaideas.org/emergency_books/2.

State-Level and System-Level Guidance

Michigan Department of Community Health, Office of Public Health Preparedness. Guidelines for Ethical Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources and Services during Public Health Emergencies in Michigan. Vol. 2. November 2012. https://www.mimedicalethics.org/Documentation/Michigan%20DCH%20Ethical%20Scarce%20Resources%20Guidelines%20v2%20rev%20Nov%202012.0.pdf.

Minnesota Department of Health. Minnesota Crisis Standards of Care Framework: Ethical Guidance. January 10, 2020. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ep/surge/crisis/framework.pdf.

Minnesota Department of Health. Minnesota Crisis Standards of Care Framework: Health Care Facility Surge Operations and Crisis Care. March 1, 2020. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ep/surge/crisis/framework_healthcare.pdf.

Minnesota Department of Health. Patient Care: Strategies for Scarce Resource Situations. May 2019. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ep/surge/crisis/standards.pdf.

New York State Department of Health, New York State Task Force on Life and the Law. Ventilator Allocation Guidelines. November 2015. https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/task_force/reports_publications/docs/ventilator_guidelines.pdf.

Veterans Health Administration’s National Center for Ethics in Health Care, Pandemic Influenza Ethics Initiative Work Group. Meeting the Challenge of Pandemic Influenza: Ethical Guidance for Leaders and Health Care Professionals in the Veterans Health Administration. July 2010. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/pandemicflu/Meeting_the_Challenge_of_Pan_Flu-Ethical_Guidance_VHA_20100701.pdf.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary of Preparedness and Response (ASPR), Technical Resources, Assistance Center, and Information Exchange (TRACIE)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “ASPR TRACIE Resources.” https://asprtracie.hhs.gov/.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, TRACIE. “Healthcare Coalition Influenza Pandemic Checklist.” 2019. https://asprtracie.hhs.gov/technical-resources/resource/4536/health-care-coalition-influenza-pandemic-checklist.

See also:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ethical Considerations for Decision Making regarding Allocation of Mechanical Ventilators during a Severe Influenza Pandemic or Other Public Health Emergency. July 1, 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/about/advisory/pdf/VentDocument_Release.pdf.

Additional Guidance on Resource Allocation and Disaster Response

A. H. Matheny Antommaria et al. “Ethical Issues in Pediatric Emergency Mass Critical Care.” Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 12, no. 6, supplement (2011): S163-S168. https://journals.lww.com/pccmjournal/Fulltext/2011/11001/Ethical_issues_in_pediatric_emergency_mass.9.aspx.

M.D. Christian et al. “Development of a Triage Protocol for Critical Care during an Influenza Pandemic.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 175, no. 11 (2006): 1377-81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1635763/pdf/20061121s00015p1377.pdf.

S.K. Cinti et al. “Pandemic Influenza: The Ethics of Scarce Resource Allocation and the Need for a Hospital Scarce Resource Allocation Committee.” Journal of Emergency Management 8, no. 4 (2010). https://wmpllc.org/ojs/index.php/jem/article/view/1337.

E. L. D. Biddison et al. “Too Many Patients . . . a Framework to Guide Statewide Allocation of Scarce Mechanical Ventilation during Disasters.” CHEST 155, no. 4 (2019): 848-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2018.09.025.

J. L. Hick et al. “Clinical Review: Allocating Ventilators during Large-Scale Disasters—Problems, Planning, and Process.” Critical Care 11, no. 3 (2007): 217. https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/cc5929.

J. Y. Lin and L. Anderson-Shaw. “Rationing of Resources: Ethical Issues in Disasters and Epidemic Situations.” Prehospital Disaster Medicine 24, no. 3 (2009): 2l5-21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X0000683X.

G. Persad, A. Wertheimer, and E. J. Emanuel. “Principles for Allocation of Scarce Medical Interventions.” Lancet 373, no. 9661 (2009): 423-31. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(09)60137-9/fulltext.

J. Tabery, C. W. Mackett, and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Pandemic Influenza Task Force’s Triage Board. “Ethics of Triage in the Event of an Influenza Pandemic.” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2, no. 2 (2008): 114-18. https://doi.org/10.1097/DMP.0b013e31816c408b.

Institutional Ethics Services

W. G. Anderson et al. Hospital-Based Prognosis and Goals of Care Discussions with Seriously Ill Patients: A Pathway to Integrate a Key Primary Palliative Care Process into the Workflow of Hospitalist Physicians and Their Teams. February 2017. Implementation guide: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/globalassets/clinical-topics/clinical-pdf/ctr-17-0031-serious-illness-toolkit-m1.pdf.

N. Berlinger, B. Jennings, and S. M. Wolf. “Guidelines for Institutional Policy,” part 2, section 6 in The Hastings Center Guidelines for Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care Near the End of Life, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

D. M. Hester and T. Schoenfeld, eds. Guidance for Healthcare Ethics Committees. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

|

In 2006, The Hastings Center partnered with Providence Center for Health Care Ethics at Providence Health & Services (Portland, OR) to explore foreseeable challenges in responding to pandemic influenza. On September 25, 2006, The Hastings Center hosted an international convening of public health officials, clinicians, and ethics and policy scholars to consider how pandemic preparedness should reflect ethical considerations, drawing on lessons from public health emergencies such as SARS in 2003-04 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Our work focused on hospitals as health care providers, as employers, and in relation to public health authorities and other health care settings. Hastings Center staff, in consultation with convening participants, produced a discussion tool and other publications for use by hospitals and regional health authorities. The discussion tool was subsequently included in Promising Practices: Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Tools, a peer-reviewed database maintained by the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) and the Pew Center on the States. The 2006 convening and publications were made possible by a grant from the Providence St. Vincent Medical Foundation. With the emergence and spread of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and resulting disease state COVID-19, The Hastings Center has revisited this work, convening a special advisory group (see Contributors) to produce this Ethical Framework with supporting Guidelines for Institutional Ethics Services. This rapid-response work is made possible by the Donaghue Impact Fund at The Hastings Center. |

Quick Reference: Public Health Authorities during an Infectious Disease Outbreak

The federal National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza,[1] its detailed Implementation Strategy,[2] and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Pandemic Influenza Plan[3] describe the roles and responsibilities of the federal, state, and local authorities before, during, and after infectious disease outbreaks. During an outbreak, responsibilities will include (1) surveillance and detection and (2) response and containment.

Surveillance and Detection

- HHS is primarily responsible for supporting laboratory capacity and diagnostic testing to provide rapid confirmation of cases, as well as for creating the mechanisms for clinical surveillance in acute care settings and keeping public health officials aware of the epidemiological profile and spread of the illness.

- Hospitals, clinics, and health care systems must develop relationships with their local public health departments to facilitate the flow of rapid diagnostic tests and clinical surveillance data to and from federal and state agencies.

Response and Containment

- HHS and other federal partners will coordinate to provide state and local authorities with guidance on community containment strategies, including social distancing, quarantine, and other infection control campaigns.

- Prior to the outbreak, state, local, and tribal authorities will have developed public health and medical surge plans in partnership with HHS and major medical societies and organizations.

- HHS has encouraged the formation of Health Care Coalitions (HCCs), comprised of health care and response organizations such as hospitals, emergency medical services, public health agencies, and others.

- During an outbreak, hospitals, health care systems, and HCCs should be prepared to activate these plans to care for a large number of patients in the event of escalating transmission of disease, including noninfected patients.

- Hospital and health care systems must also prepare for continuity of operations in the event that their supply chain is disrupted. This will require coordination with state and local authorities responsible for maintaining stockpiles of necessary items, including food, fuel, water, and N95 respirators.

- HHS will disseminate recommendations for the use of antiviral stockpiles and will coordinate with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to allocate antiviral drugs, vaccines, and other medical countermeasures when available.

- HHS is responsible for ensuring that timely, clear, and coordinated public health messaging is delivered to the American public. The communication strategy from HHS should guide the response by state and local authorities, as well as hospitals and health systems.

[1] United States Homeland Security Council, National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza, November 2005. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/pandemic-influenza-strategy-2005.pdf.

[2]United States Homeland Security Council, National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza: Implementation Plan, Mary 2007. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/pandemic-influenza-implementation.pdf.

[3]United States Department of Health and Human Services, Pandemic Influenza Plan: 2017 Update. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/pan-flu-report-2017v2.pdf.

Contributors

Project Director: Nancy Berlinger, PhD*

Research Scholar, The Hastings Center

Bioethics Committee, Montefiore Medical Center

The following individuals are coauthors of this document. Their institutional affiliations are provided for purposes of identification only.

Jean Abbott, MD, HEC-C

Professor Emerita, Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado

Ethics Committee, University of Colorado Health

Lori Bruce, MA, MBE

Chair, Community Bioethics Forum, Yale School of Medicine

Associate Director, Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics, Yale University

Elizabeth J. Chuang, MD, MPH

Associate Professor, Department of Family and Social Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center

Clinical Ethics Research Faculty, Montefiore Einstein Center for Bioethics

Felicia Cohn, PhD, HEC-C

Clinical Professor of Bioethics, Irvine School of Medicine, University of California

Bioethics Director, Kaiser Permanente Orange County

Rachel Fabi, PhD

Assistant Professor, Center for Bioethics and Humanities, SUNY Upstate Medical University

Laura K. Guidry-Grimes, PhD

Clinical Ethicist, Assistant Professor of Medical Humanities and Bioethics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

D. Micah Hester, PhD

Chair, Department of Medical Humanities and Bioethics, and Professor of Medical Humanities and Professor of Pediatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Nancy Piper Jenks, MS, CFNP, FAANP

Medical Site Director of Internal Medicine, HRHCare, Peekskill, NY

Aimee Milliken, RN, PhD, HEC-C

Clinical Ethicist and Nurse Scientist, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Grace Oei, MD, MA, HEC-C

Director of Clinical Ethics, Loma Linda University Health

Attending Physician, Division of Pediatric Critical Care, Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital

Tia Powell, MD**

Director, Center for Bioethics and Masters’ in Bioethics, Montefiore Health Systems and Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Professor of Epidemiology and Psychiatry, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Jamie Carlin Watson, PhD

Clinical Ethicist, Assistant Professor of Medical Humanities and Bioethics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP**

Professor, Schools of Medicine and Public Health, Director, Center for Bioethics and Humanities, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO

*Codirector, Hastings Center convening, Addressing Pandemic Planning in Clinical Ethics Education, September 25, 2006.

**Participant, Hastings Center convening, Addressing Pandemic Planning in Clinical Ethics Education September 25, 2006.

Research Assistant: Bethany Brumbaugh

Editors: Gregory E. Kaebnick, Laura Haupt

Designer: Nora Porter

Communications: Mark Cardwell, Susan Gilbert, Julie Chibbaro